News & Highlights

Topics: Child Health, Clinical & Translational Research, Five Questions, Funding, Pilot Funding

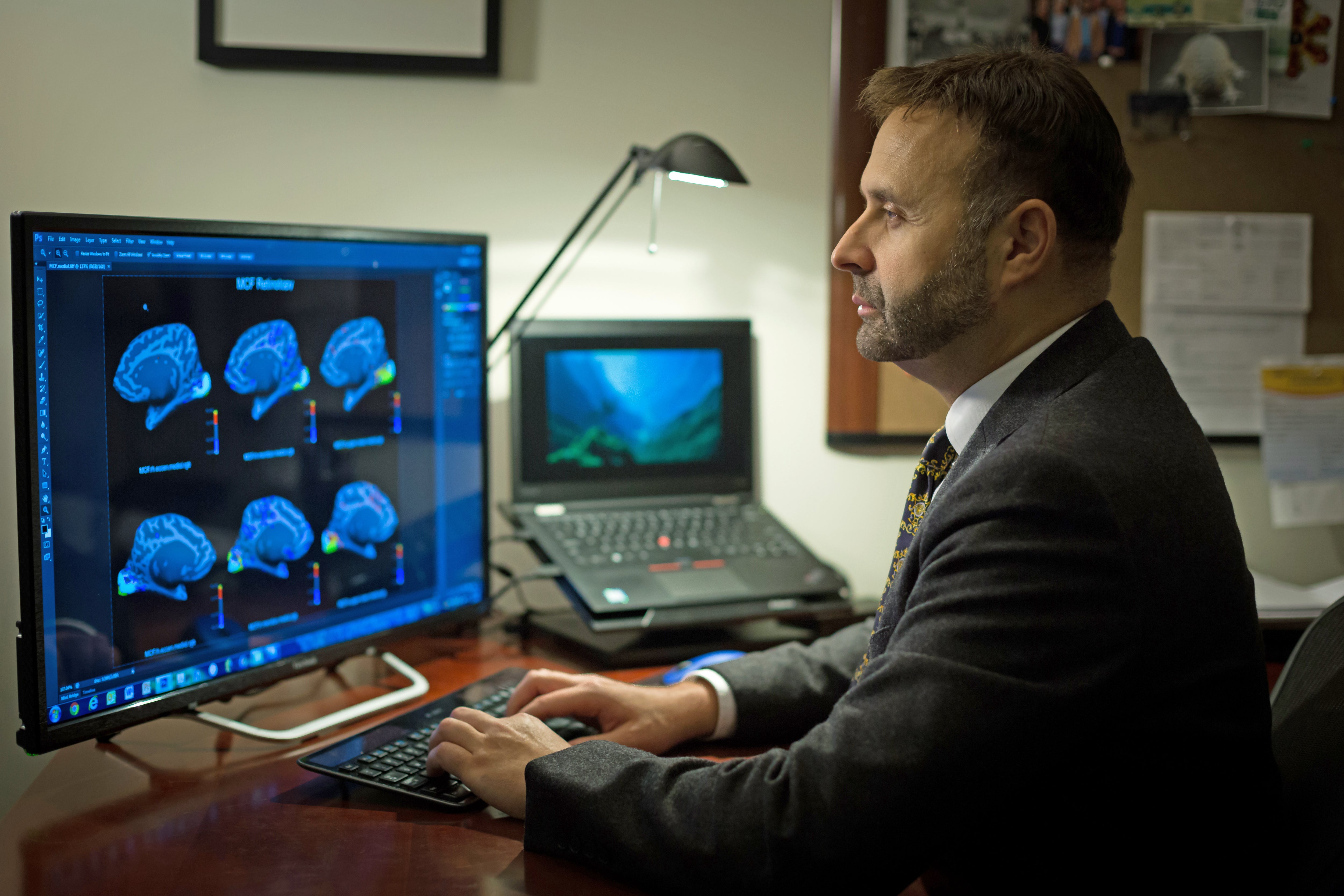

Five Questions With Lotfi Merabet

Our Sight and Science awardee talks visual impairment, vision, collaboration, and communication.

Try this simple experiment: Blindfold yourself. Wherever you are, allow yourself to be temporarily without sight. What will you do? Will you just sit still the whole time? How will you navigate the space? What if there’s an important call? What are you going to do if the fire alarm goes off, or you smell smoke, and have to leave the building quickly? How do you use your other senses to compensate for what you can’t see?

Lotfi B Merabet, OD, PhD, associate professor of ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School and associate scientist at Massachusetts Eye and Ear and Schepens Eye Research Institute, uses this mental experiment in his talks on blindness. Merabet received pilot funding as part of our Sight and Science: Vision 2020 for his research aimed at finetuning a promising gene therapy for cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy (cALD), a rare but devastating genetic disorder in children. The project investigates whether a novel virtual reality platform might identify visual deficits early so doctors can intervene at the right time to stop the disease’s progression.

You study a subset of visual impairment and blindness, cerebral visual impairment (CVI), which originates in the brain as opposed to the eyes. How has blindness changed over time, and why?

I can speak of my experience at the Perkins School for the Blind. Five or six decades ago, the typical child attending Perkins was born blind due to a problem with their eyes. They came to Perkins and learned Braille, they learned to walk with a cane, and so on. Over the past 20 years or so, that profile has changed. The children who attend the school now look very different. They have blindness or visual impairment not necessarily because of eye issues but because of damage within their brains. We’ve noticed that many struggle to learn Braille and they struggle to learn how to use a cane. All of a sudden, the classic tried-and-true curriculum doesn’t seem to be working anymore and clearly it needs to be adapted.

CVI is now the number one cause of pediatric visual impairment in the United States. In adults, blindness and visual impairment are more commonly about the eye, but in the kids, it’s about the brain. That is fundamentally different. The strategies and tools we need to assess and diagnosis these individuals are also going to be very different. We now need a whole new way of thinking and a whole new way of doing things.

“CVI is now the number one cause of pediatric visual impairment in the United States.”

We’re victims of our own success. Overwhelmingly, children with CVI are often born prematurely or had some sort of perinatal complication and we’re getting very good at saving these kids. They weren’t surviving 30 or 40 years ago. Today, they’re surviving in large numbers, as awareness about CVI grows and as intensive neonatal care improves. Now we have this whole new population that is surviving and thriving, but they require new paradigms in education and habilitation. That’s the conundrum.

Your 2014 Ted Talk proposed that blindness is “just another way of seeing.” What did you mean?

There’s a great quote that says the reason you have a brain is so you can use the past to predict the future. Everybody creates this model in their mind about what the world is like. How that model is created is largely driven by your experiences, which is different for everyone. If you’re born without sight, hearing, or a limb, how does the brain create that model? And is that model fundamentally different? Even in the case of blindness, it doesn’t mean that that model is so impoverished that you can’t lead a full and independent life.

Helen Keller said that just because you don’t have sight doesn’t mean you don’t have vision. She was blind and also deaf, but she was still able to form a construct of the world in her mind and lead a very productive life. That’s what matters.

What was your research question in your Sight and Science pilot grant project and why did you choose it?

The story starts with my colleague Florian Eichler, a pediatric neurologist at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), who works specifically with this population of cALD. In 2017 Florian authored a pivotal paper in the New England Journal of Medicine detailing a gene-based therapy that could halt the progression of this disease, so these children could get their lives back. This was absolutely monumental. There was a lot of excitement. A large gene therapy center launched at MGH.

So now we’ve got this great therapy, but a big question remains about the best timing for administering it. If we give it too late, brain damage may already be too extensive, because it halts the progression of the disease; it doesn’t necessarily reverse it. But giving it too early is not an option either because of what you have to put the children through – a bone marrow transplant and experimental gene therapy. You would not want to treat a child unless they absolutely need it. Only about half of children who have the gene manifest the disease. Interestingly, one of the first complaints reported by children with cALD is related to their ability to visually process the world around them.

“What Harvard Catalyst gave us is the opportunity to put our heads together with individuals that we may not necessarily meet.”

So he has this incredible treatment but he doesn’t know when the optimal time is to give it. He needed a better way to pick the moment. When he saw what we were doing to diagnose visual processing deficits in CVI using virtual reality, he said, that might be the signal I’m looking for. That’s how we began our collaboration.

What do you see as the value of collaborations like this one?

What Harvard Catalyst gave us is the opportunity to put our heads together with individuals that we may not necessarily meet; now we have a chance to explore this signal. Meeting gives you an opportunity to ask: Is there something here before we really commit to a large scale study? There’s a big difference between the first date and proposing for marriage. This project is the first date. It gives you a chance to see if there’s some chemistry before you get engaged.

Why do you conduct clinical/translational research?

To make the world a better place. I think everybody should leave the world slightly better than how they found it. You can choose how to do that, but that’s what this is about. If one kid has a better outcome because of our study, we did our job. If one kid can get the support and the education that he or she deserves, we’ve done our job. If one family feels that their child will be taken care of and will be getting the best possible treatment at the right time, we’ve done our job.