News & Highlights

Topics: Five Questions, Innovation & Science, Pilot Funding, Technology

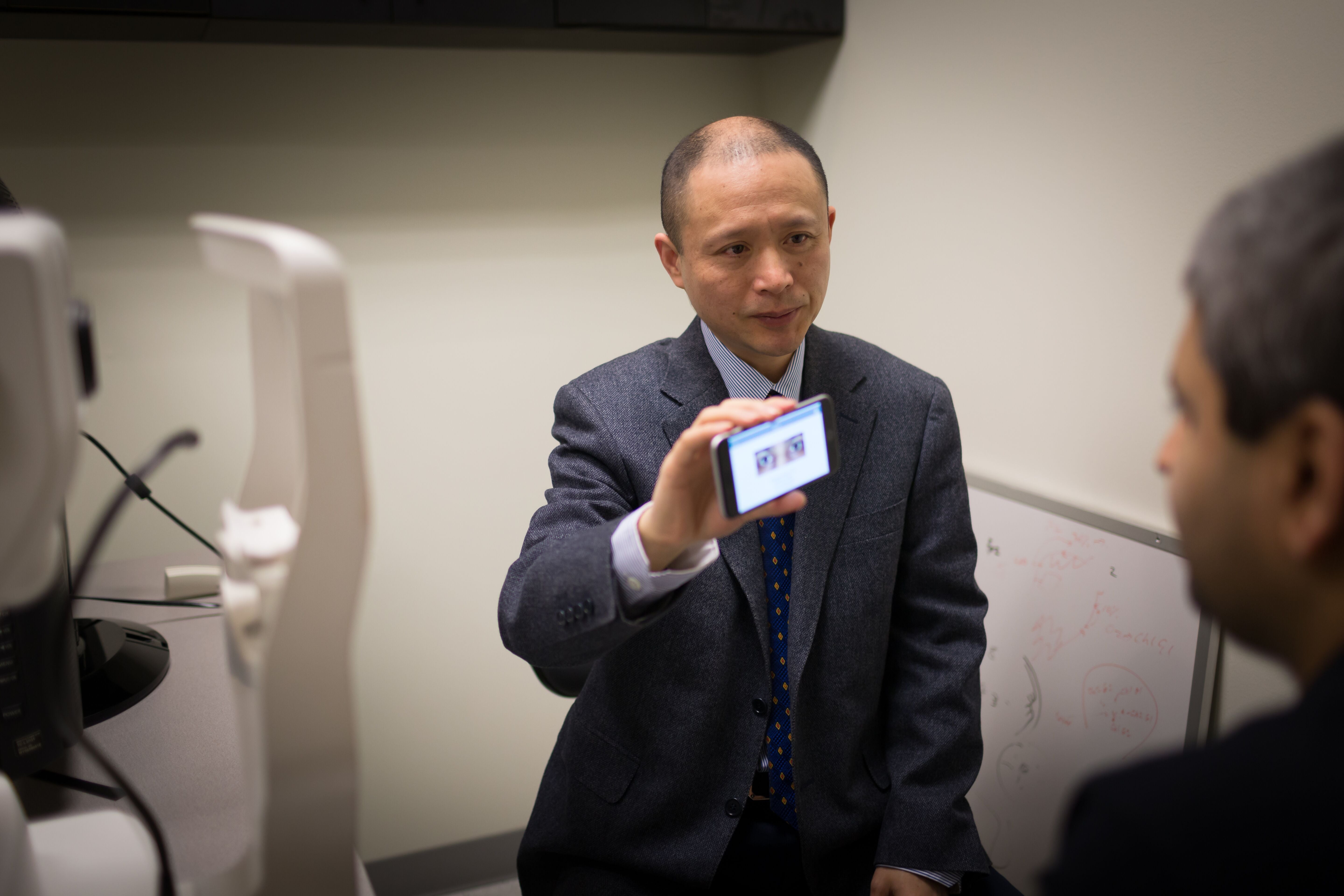

Five Questions with Gang Luo

Our Sight & Science pilot funding awardee discusses his research using smartphone technology to assist the visually impaired.

Gang Luo, PhD, associate professor of ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School and Schepens Eye Research Institute, received one of our Sight & Science 2020 awards for his pilot project, “Mass screening of myopia using smartphones.”

As a research engineer originally from China, how did you became interested in the human visual system and end up working at Schepens Eye Research Institute?

As an engineer, I did a lot of image processing and computer vision work, which led to my interest in human vision. Eighteen years ago, I came to Harvard Medical School as a postdoc at Schepens and received training in low vision and vision science. Since then, I have been working on many projects that combine my engineering expertise with my research focus in vision. Currently, I develop assistive technology for vision-impaired people, and also study their walking and driving.

I really love the Harvard Medical School environment and Boston. I’ve never thought about going anywhere else. I came here with my wife and, 10 years ago, my daughter was born.

What’s an example of assistive technology you have developed?

We just wrapped up a clinical trial on a wearable collision warning device. In this clinical trial, we gave blind individuals this device to take home and wear wherever they walked, went to work, or as they shopped. Many blind people use long canes or a guide dog to help them avoid collisions. But there are limitations. Long canes, for example, may take care of obstacles at ground level but miss high-level obstacles. Our device has a camera monitor at chest level, and when a hazard is detected, it gives them a warning on a vibrating wristband. Our findings aren’t published yet, but we found that the device appears to help reduce collisions.

Talk about your Harvard Catalyst project and how you decided to use smartphones as a platform.

Six years ago, I started to focus on assistive technology based on smartphones. It’s a great platform that easily delivers the technology. We’ve developed four smartphone apps for low-vision people, which can help them to do things such as access public transportation. We have developed dedicated devices, but unless they are commercialized, patients don’t get to benefit from them. Technology based on a smartphone can be immediately released to the app store. There have been more than a million downloads for the four apps we’ve developed so far. I’m very glad that we’re making a real impact and helping our patients.

[View links to Luo’s SuperVision Magnifier, SuperVision Goggles, and SuperVision Search apps, all of which are free.]

It’s the same idea for the Harvard Catalyst pilot project. It’s a smartphone app people can use to measure refractive error. So if a person is myopic, or near-sighted, and they want to check their prescription or see if the myopia has progressed, they can use this smartphone app at home to measure it using their own phone. You don’t need any special optical attachment. Once you download it, you can use it immediately, which I think is very important.

Our app uses the selfie camera and can measure refractive error, IPD (the distance between eyes), and vision acuity, like the traditional eye chart.

“There have been more than a million downloads for the four apps we’ve developed so far.”

We want to show that it could be used by people without a medical background, as part of the annual vision screening conducted at schools, for example. We’re recruiting patients from different locations for the pilot study and will have parents and medical professionals use the app to do a measurement once every month. We want to compare and see how accurate and consistent the measurements are. We also hope to catch children with myopia early or myopia that is progressing very fast.

My Harvard Catalyst project has been selected by the “Lab to Market” course at Harvard Business School as a project for a group of MBA students. They will help come up with a business plan to commercialize the refraction measurement technology.

Close to 42% of Americans have myopia, and in parts of Asia, about 80-90% of those who finished 12 years of school have it. How will this app help this growing problem?

This technology could address a few problems. Since we are still in the COVID-19 pandemic and myopia is not a life-threatening condition, vision care can get delayed. In clinic appointments, the doctor can do all the vision tests for acuity, refractive error, and so on, but when you’re at home, you can only talk to the doctor via telemedicine. We hope to bring clinical testing to your home. That way, telemedicine will become more helpful to patients.

It could also help with vision screening in schools. Schools are supposed to do vision screening every year in the U.S., China, and many other countries. But typically, myopia is not measured in the screening because it requires someone with expertise to measure refractive error. There are hundreds of millions of students in China or the U.S. It’s just not possible to rely on medical staff to do all the vision screening.

How are you and your family in China faring through the pandemic? What activities do you do to stay balanced?

We have a big family in China who are doing fine. The pandemic is almost over in China, and they’re traveling without any big concerns. I don’t need to worry about them.

I’m working mainly from home and go into the lab when needed. Without spending two-and-a-half hours commuting, my time is a bit more flexible. I used to enjoy music lessons and now I use some of that extra time, say around 6:00 pm, to take lessons on the cello. Usually at 6:00 pm, I was on my way home or I needed to pick up my daughter.