News & Highlights

Topics: Community Engagement

Tapping Community Insights to Improve Research Diversity

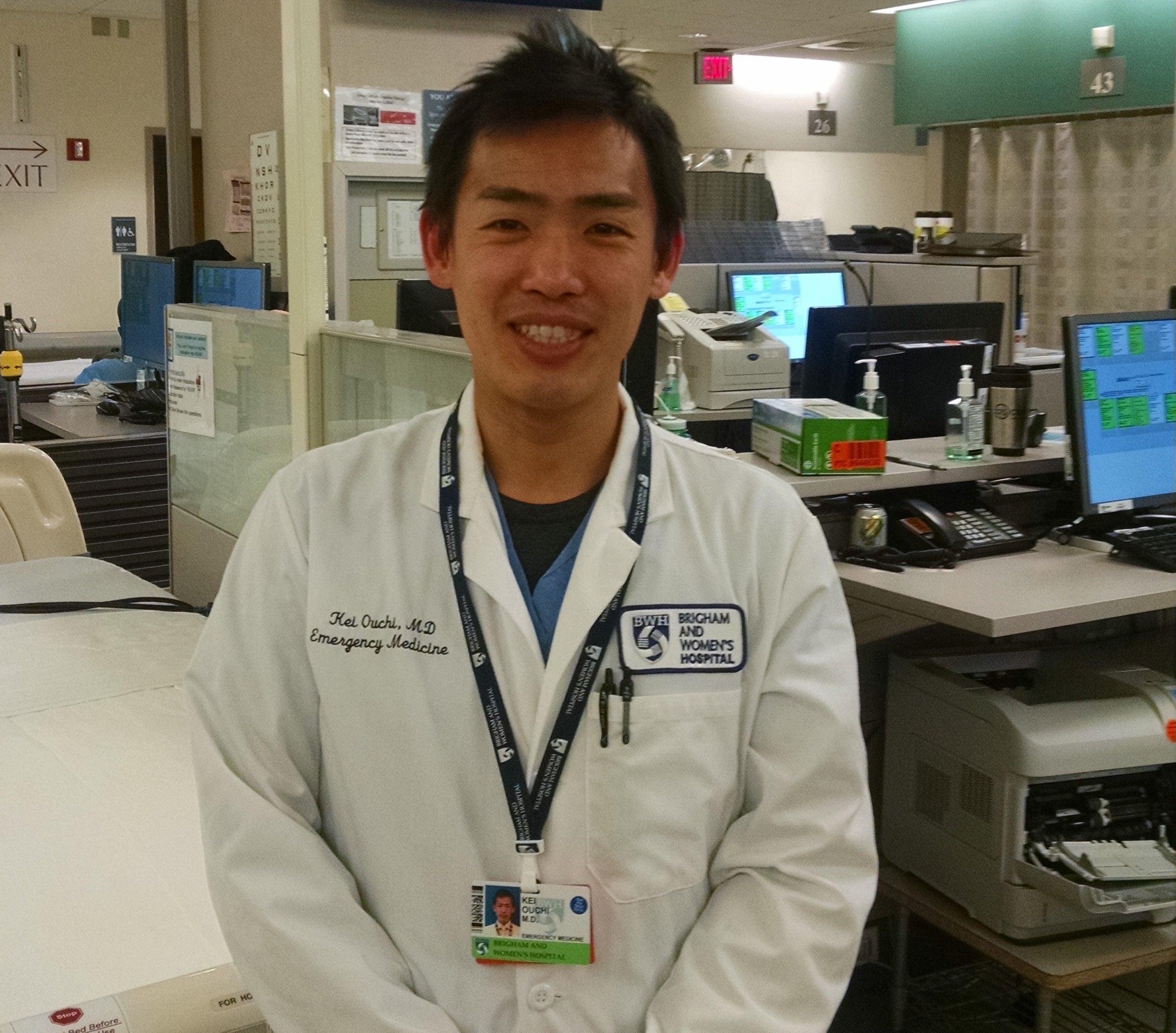

Five Questions with Kei Ouchi on collaborating with the Community Coalition for Equity in Research.

Improving diversity in clinical research is a national and international research goal seen as imperative to combating healthcare disparities and inequities. But for boots-on-the-ground researchers like Kei Ouchi, MD, MPH, delivering meaningful results can be daunting.

Ouchi, an emergency physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, was faced with an imperative: recruit and retain more participants who self-identify as Black and Latinx into his study, which aims to improve end-of-life care planning among seriously ill patients who are seen in the emergency department. But he’d had no success with past efforts and, as a native of Japan, no experience in reaching or working with these populations.

Enter the Community Coalition for Equity in Research, an initiative through Harvard Catalyst’s Community Engagement program that seeks to engender trust-based, respectful relationships between researchers and community organizations and members. The Coalition’s study review service unlocked some key strategies to tackle deep-rooted distrust of the medical establishment among these communities and design the study for optimal inclusion of the populations of interest. This work also jump-started ongoing collaborations to improve cultural competency among research staff.

What gap does this research seek to fill?

The research I’m working on tries to help patients living with serious life-limiting illness formulate and communicate their goals for end-of-life care. We see a lot of these patients coming to the emergency department in the weeks or months before their death, so it’s an opportunity to intervene.

This care planning (i.e., advance care planning) is not done routinely in our country, and even less frequently among ethnically and culturally minoritized population groups. I’ve been studying this topic with grant support from the National Institute on Aging. In our prior study, about 90% of participants were white, non-Hispanic older adults. That’s not anywhere close to the population demographic of our country. I wanted to remedy that, but I had no prior experience with this kind of focused recruitment.

Our initial focus is on populations with the largest proportions, which are Black and Latinx patients, based solely on patient self-identification. Down the line, we will try to focus on other populations as well.

I am from Japan. I don’t know anything about working with older Black Americans and Latinx populations. I’d never done it before.

How did you get connected with the Coalition and what was the study review process like?

I stumbled across the Coalition either on the Harvard Catalyst website or in an announcement. When I looked into it, I thought: This makes so much sense. Ask the experts to approve the study design before you actually do it.

“At the meeting where I presented my project, I was pleasantly surprised to see so many faces from so many different backgrounds thinking about this issue, engaged in my presentation, and brainstorming with me.”

I don’t think there are many services like this that are offered routinely at other institutions, or maybe not as extensive as this one. This is a strength of our academic healthcare network, so as researchers we need to leverage that.

I submitted my request for a study review, they granted it, and then I sent the summary of my study. I sought advice for any considerations I hadn’t thought about or formulated yet in writing. At the meeting where I presented my project, I was pleasantly surprised to see so many faces from so many different backgrounds thinking about this issue, engaged in my presentation, and brainstorming with me. Each member brought their own perspective to the table. A written summary of the recommendations was provided afterward, which was really helpful. These interactions definitely help me to shape my science better and formulate more effective recruitment strategies.

Usually, you get this kind of feedback the hard way: You start doing it and it’s not working, so you start to ask why. It was serendipitous to find this resource at this stage.

What about the review was most helpful to you?

For researchers like me who haven’t worked with diverse populations, it has been really helpful in refining research aims, design, and execution to try to approach a population that I don’t know anything about.

One challenge for a study like mine is that we don’t know exactly which patients are going to come to the emergency department. Even so, Coalition members advised me to establish partnerships with local community-based organizations and primary care providers before I begin the study to see if I could enlist their help. They said underserved populations sometimes have better connections or more trusting relationships with community-based organizations than with the medical system. That was really helpful.

My study’s aim is to help patients get excited about thinking about their future care and documenting their wishes for end-of-life care. That requires they continue to have this discussion with family and friends as well as their primary care physician. But social support systems vary, and some people don’t have a primary care physician. Sometimes all they have are these trusted, community-based organizations.

The Coalition recommended we ask the patients if they have that type of organization in their community and if so, to involve those organizations in our planning. That was something I had not thought of.

How has your approach to research changed as a result of the Coalition’s review?

I was specifically advised to create a research team with similar racial, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds as the study participants. I have collaborators who are Black and Latinx patients, and I have to be more mindful about involving them in specific ways. That also applies to the co-investigators, research assistants, nurse clinicians, and anyone else involved in the study. How would they conduct the intervention? What language would they use?

Another recommendation was to conduct systemic trainings in cultural competency, cultural curiosity, and racial disparity for myself and my research staff. This will help us approach and enroll patients with more respect for their cultures. Some cultures may not find value in formulating and discussing their end-of-life care preferences. For some, specifically addressing religious and spiritual beliefs up front might be helpful in trying to establish a therapeutic alliance between research team and patient.

“We cannot ignore populations that make the research harder to complete.”

I learned that a proactive approach may also be helpful in addressing the well-documented historical distrust of medicine among Black patients. Is it better to address that up front when we recruit patients? What is the best way to approach the subject? I think that’s something we need to explore.

Moving forward, I’ve asked some interested Coalition members to meet with me regularly to help guide and execute these recommendations. We will work together to design the cultural competency trainings and explore these questions around study design, to leverage their expertise before I begin the study. I’m looking forward to learning more from them.

Diversity research such as you’re doing is notoriously challenging to conduct. Why take this on now?

It’s harder to do research with ethnically and culturally minoritized older adults, but that doesn’t mean we can pretend they don’t exist. We cannot ignore populations that make the research harder to complete. If you do, you are never going to study the populations that actually represent our country.

As a researcher, there’s always a tension between the feasibility of actually finishing a study versus capturing all the populations that we need to study. We want to conduct a scientific study that will produce results that are interpretable, right? If you cannot follow up with patients, then you can’t complete the study, which won’t answer the question of the research.

Even with all these things that we will do to improve diversity, it’s unlikely to be perfect. It might not have as good a follow-up rate, for example. You just have to strive to get there. This is one attempt to do so.