News & Highlights

Topics: Diversity & Inclusion, In the News

Addressing Workforce Diversity — A Quality-Improvement Framework

"Workforce diversity in medicine, particularly at the highest levels of health care leadership, remains an elusive goal," write authors Lisa S. Rotenstein, MD, MBA, Joan Y. Reede, MD, MPH, MBA, and Anupam B. Jena, MD, PhD in The New England Journal of Medicine.

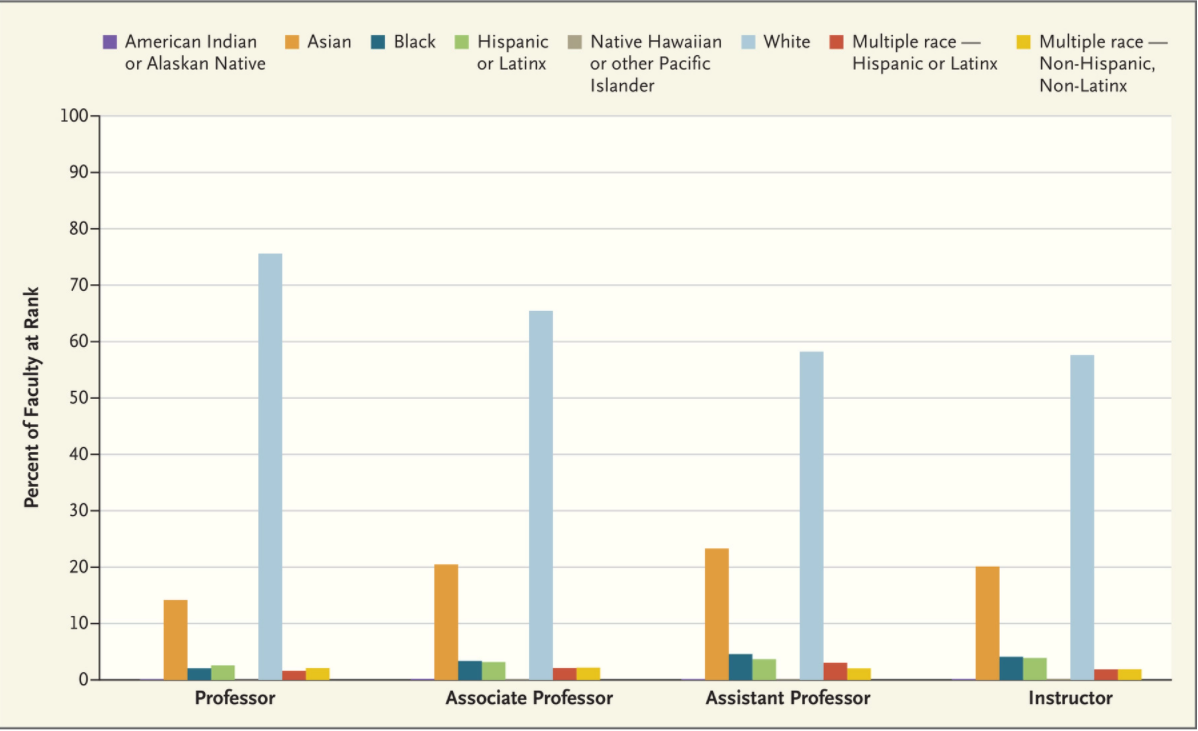

Workforce diversity in medicine, particularly at the highest levels of health care leadership, remains an elusive goal. In the United States, 3.6% of medical school faculty are Black, 3.3% are Hispanic or Latinx, and 0.1% are American Indian or Alaskan Native, according to data from the Association of American Medical Colleges (see graph); those groups comprise 13.4%, 18.5%, and 1.3% of the population, respectively. Female physicians make up more than half of most graduating medical school classes but account for only 5.5% of full professors and 26% of department chairs. Although increased attention is being paid to issues related to workforce diversity, equal representation in health care is hampered by organizational actions and inaction, structural racism, and unequal opportunity throughout the education continuum.

“Although increased attention is being paid to issues related to workforce diversity, equal representation in health care is hampered by organizational actions and inaction, structural racism, and unequal opportunity throughout the education continuum.”

Lack of workforce diversity has detrimental effects on patient outcomes, access to care, and patient trust, as well as on workplace experiences and employee retention. A substantial number of White medical students and residents hold biased views about race-based differences in pain perception that affect their treatment recommendations, for example.1 Patient race and sex influence the way in which physicians treat chest pain.2

The evolution of the modern quality movement represents a useful parallel for achieving a complicated goal like equal representation in health care. The early years of the quality movement were focused on defining the problem. To Err Is Human, the 1999 landmark report from the Institute of Medicine (IOM), created a moral imperative for enhancing patient safety by documenting that as many as 98,000 U.S. deaths each year were caused by medical errors in hospitals. That same year, the National Quality Forum (NQF) was founded; the organization later established definitions for “never events” (adverse events that should never occur) and “safe practices.” In 2001, the IOM published Crossing the Quality Chasm, which outlined a systematic framework for measuring quality (based on structure, process, and outcomes) and specified six goals of quality improvement.3

The next stage of the quality movement focused on measurement, with federal agencies guiding the development of quality measures and the NQF establishing a performance-measurement endorsement process and national performance measures. Developing and defining measures facilitated reporting and transparency efforts, such as the Hospital Compare website from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the NQF’s voluntary consensus standards for hospital-based measurement. Implementation of these measurement tools put pressure on institutions to outperform their peers.

Today, in all health care systems, measures of quality and safety—such as Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems data and rates of hospital-acquired infections—are presented to health care leadership and used to evaluate leaders. Ensuring high quality is not only a moral imperative, it is now also a business imperative. Organizations have responded by implementing systematic quality-measurement and process-improvement efforts.

Key principles emerge from this journey for achieving goals related to workforce diversity. Although the moral imperative for diversity has become clearer, the next stage involves tying rigorous measurement and outcomes to incentives that move relevant actors toward action.

As a first step, we believe that disaggregated data on workforce diversity and the experience of underrepresented and historically marginalized faculty should be regularly collected by organizations and reported to executives and board members. Organizational leaders should then make the pursuit of diversity a shared responsibility that extends down the chain of command. A similar call for defined executive responsibility related to patient safety was included in Crossing the Quality Chasm.3 Today, data on falls, health care–associated infections, and errors are reported, discussed, and acted on at the highest levels of health system leadership, with responsibility for quality of care flowing to nursing, physician, administrative, and other leaders at all levels. Similarly, metrics related to workforce composition and to retention, promotion, and satisfaction of underrepresented and historically marginalized trainees, faculty, technical staff, and administrative leaders should be regularly reviewed by leaders, tracked over time, compared among groups, and discussed at the highest levels.

These data should be used to catalyze action. Workforce-diversity measures, including measures related to structure, process, and outcomes, should be tied to executive evaluation and compensation.

Structural measures could include the existence of an executive-level position devoted to diversity, equity, and inclusion, with funding and staff to support these efforts; the presence of programs to promote career satisfaction and ensure support for underrepresented and historically marginalized faculty; and the availability of pipeline or recruitment programs for underrepresented health care professionals.

Process measures could include the number and type of groups to which available positions are publicized, the number of minority and female candidates interviewed for each position (particularly leadership positions), dedication of space for workforce-diversity metrics in annual reports, and actions taken to address reports of problems with organizational culture or climate or to rectify inequities identified in reviews of internal data.

Outcome measures might include statistics related to faculty diversity; the gender, racial, and ethnic makeup of committees in charge of funding- and policy-related decisions; student and trainee reports on organizational culture and climate; faculty promotion and retention; pay equity; and job satisfaction. This approach is increasingly being used in the technology industry, such as at Microsoft, where the chief executive’s bonuses are partially tied to diversity goals. Whether such incentives improve workforce diversity and culture hasn’t been determined.

Second, workforce-diversity data should be publicly reported. The publication of data on hospital-acquired infections catalyzed increased attention to infection metrics, and the decision by U.S. News and World Report to give hospitals credit in its ranking system for publicly reporting data on cardiovascular and thoracic surgery outcomes spurred increased visibility of these outcomes. In the same way, public attention to diversity data could be a powerful catalyst for action. The Lown Institute’s recent national ranking of hospitals based on civic leadership, value of care, and patient outcomes stirred discussion because of its emphasis on care for the community and its stark contrast with the U.S. News and World Report rankings. No such ranking system exists for issues related to workforce diversity, although there are opportunities to establish stand-alone listings or to integrate this dimension into current ranking methods. Although legal obstacles around reporting of workforce diversity data are unclear—particularly if this reporting attracts attention to institutions with low diversity—similar, if not more detailed, information is already openly available for many public hospital systems whose state laws mandate reporting of all state employee salaries.

Finally, individual contributions to diversity-related work should be compensated and valued in the same way as research or quality-improvement efforts are. Too often, membership on committees devoted to diversity or mentorship of underrepresented trainees or faculty members is voluntary and duties fall on the same people. If enhancing workforce diversity is an institutional priority, it shouldn’t depend on the goodwill of individual contributors, just as achievement of quality aims doesn’t rely on volunteers. Scholarship, service, and mentorship that facilitate workforce diversity should be compensated in line with other types of work related to institutional priorities, and activities that support diversity should be part of a path to academic advancement. A decade ago, clinicians sought opportunities for advancement related to quality-improvement work4; it’s now time for a career path that explicitly rewards diversity-related efforts.

The quality movement has faced barriers to scaling up initiatives, which should be considered as this framework is applied to diversity-related efforts. These barriers have included health care organizations’ primary focus on costs and revenue at the expense of quality, the predominance of volume-based payment in the United States, and the reluctance of leaders to fully embrace new outcomes-based payment models.5 These issues provide important lessons about the need for alignment of incentives and for a true leadership commitment—from the national to the local level—to catalyze concrete action toward new goals. In particular, to the extent that efforts to enhance workforce diversity may run counter to other strong financial incentives faced by organizations, as has sometimes occurred with quality-improvement efforts, these trade-offs will need to be anticipated and addressed.

Twenty years ago, the IOM called the U.S. medical community to action to prevent deaths related to low-quality care.3 Today’s challenge centers on ensuring that our health care workforce reflects our society, for the benefit of patients and clinicians alike. The experience of the quality movement suggests that progressing from exhortation to intentional action will require measurement, reporting, and adequate incentives. It will take discipline, courage, and cross-institutional commitment that may initially feel uncomfortable, but it will ultimately improve care delivery and strengthen our workforce.

Originally published in The New England Journal of Medicine.