News & Highlights

Topics: Clinical & Translational Research, Innovation & Science, Microbiome, Pilot Funding

Unexplored Frontiers

Harvard Catalyst looks at microbiome’s links to disease.

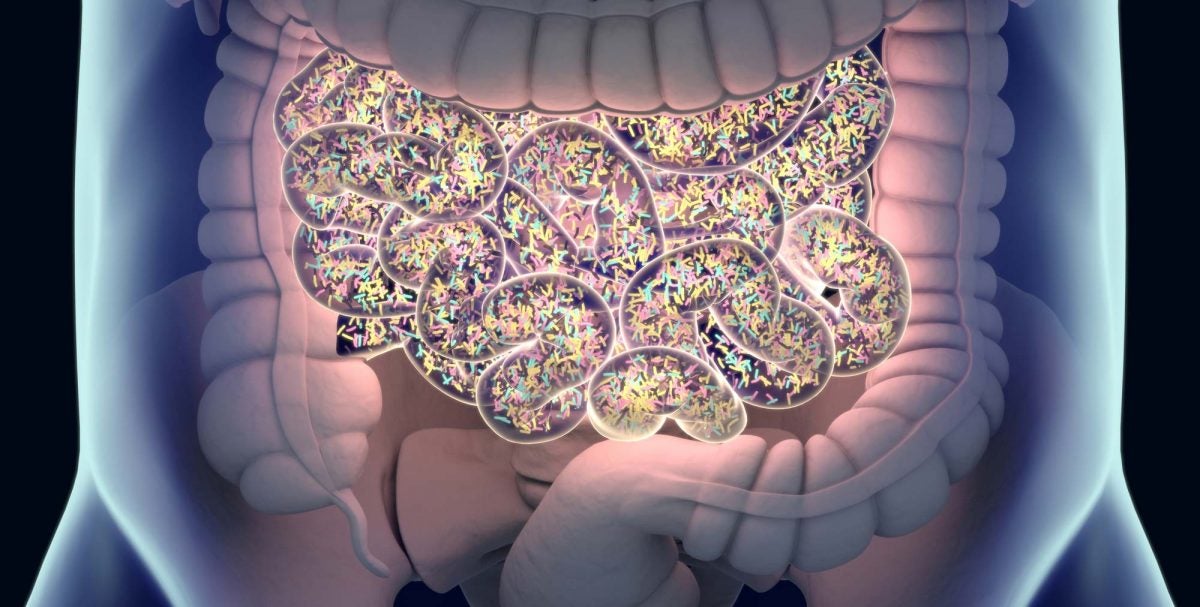

Whether or how much the gut microbiome contributes to diseases ranging from inflammatory bowel disease and colon cancer to Parkinson’s disease and diabetes was the central question scientists explored at Harvard Medical School recently as they sought to unravel some of the mysteries behind the human microbiome—a relatively unexplored frontier in scientific research.

Whether “Fusobacterium causes cancer, is an innocent bystander or is a consequence of cancer, there are obviously more questions than answers,” said Matthew Meyerson, HMS professor of pathology Dana-Farmer Cancer Institute.

Meyerson was one of several researchers who presented at the “Microbiome in Human Disease” symposium on Oct. 3. His work, Meyerson said, involves elucidating the colorectal cancer microbiome. Using a new software approach for identifying pathogens, he and his colleagues have identified an association of Fusobacterium species with colorectal carcinoma.

Sponsored by Harvard Catalyst’s Reactor program, the symposium brought together more than 350 attendees. Among them was Emily Balskus, the Morris Kahn Associate Professor of Chemistry and Chemical Biology at Harvard University, who explained how clarifying the chemistry of enzymes and metabolic pathways is helping to better understand the human microbiota.

“We haven’t yet elucidated the molecular mechanisms underlying how these organisms are influencing host biology.” Balkus said. “And this is a problem not just because of the limits of our fundamental understanding of human health and disease, but also it limits our abilities to intervene therapeutically in diseases that may be influenced by these organisms.”

“We haven’t yet elucidated the molecular mechanisms underlying how these organisms are influencing host biology.” Balskus said. “And this is a problem not just because of the limits of our fundamental understanding of human health and disease, but also it limits our abilities to intervene therapeutically in diseases that may be influenced by these organisms.”

Ashwin Ananthakrishnan, an HMS associate professor of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital who specializes in Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis and gastroenterology, explained how he and his colleagues are investigating whether the microbiome can be used as a tool to predict who will develop clinical inflammatory bowel disease, who may develop complications and who is going to respond to which therapies.

“The microbiome does appear to be a promising tool to predict disease onset, disease relapse, complications and response to therapy in irritable bowel disease,” Ananthakrishnan said. “But the story is nowhere close to ending. There are a number of unanswered questions.”

Event co-host Eva Guinan, HMS professor of radiation oncology at Dana-Farber said Harvard Catalyst’s Reactor program’s mission is to impact human health by supporting the “development, testing and adoption of novel prevention strategies, diagnostics, therapeutics and biomarkers.”

Hera Vlamakis, a research scientist at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, described her research investigating whether infants acquire bacterial strains from their mothers, whether different bacterial strains are present in disease and whether microbial species can be associated with response to treatment or disease severity.

Vlamakis noted that much of her research is based on longitudinal sampling. She also announced a recently developed database. Looking at 132 people with IBD, Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, as well as non-IBD controls, they were able to generate multiple data types. The information is available at IBDMDB.org.

Howard Weiner, the HMS Robert L. Kroc Professor of Neurology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, described how he and his colleagues are seeking to understand how the microbiome relates to multiple sclerosis.

“The gut could be the key to the cause of MS,” Weiner said.

Weiner and his team are looking into the possibility that MS could be treated by modulating the microbiome, potentially by using probiotics, specific bacteria, or with oral or nasal tolerance.

C. Ronald Kahn, the HMS Mary K. Iacocca Professor of Medicine at Joslin Diabetes Center, said the work he and his research team are conducting to better understand the role of the gut microbiome in diseases is centered around insulin resistance—diseases such as diabetes, obesity, atherosclerosis, hypertension, fatty liver disease and Alzheimer’s.

During the event, Guinan announced the establishment of the microbiome pilot funding opportunity that will award grants of up to $50,000 a year for microbiome-related research. The project’s principal investigator must have a Harvard faculty appointment, but collaborators can come from outside the institution, Guinan said.

Guinan also announced that the Harvard Catalyst website features a list of sites advertising for microbial-related research.

“These are different grant programs that we’re not affiliated with, but we’re trying to make them obvious to our research community,” she said. “I think exploring the resources outside and seeing if those are things that could support your own research or work would be an interesting opportunity,” Guinan said.