News & Highlights

Topics: Biostatistics, Five Questions

Better Living Through Biostatistics

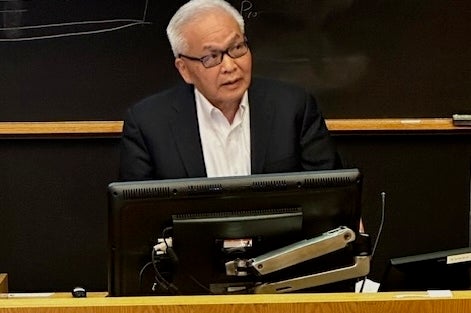

Five Questions with Biostatistician LJ Wei on why methodology matters.

After 45 years of experience finetuning clinical trial methodology to deliver clear, actionable results, LJ Wei, PhD, has a message for investigators young or seasoned: Don’t make quantitative science an afterthought.

Too often, Wei says, applying biostatistics in a research study is given a low priority or relegated to junior team members. Today’s data-driven science demands more, he argues, especially given the opportunities for applying artificial intelligence (AI) to statistical analysis. The right methodology from the beginning helps ensure that a study’s results are both transparent and translational – and actually answer the research question that is being asked.

Wei is a professor of biostatistics at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, where he has taught since 1991. When we caught up with him, he’d spent the morning learning about neural networks from Chat GPT and was excited to learn an alternative way to build prediction models beyond statistical approaches.

What is your cocktail-party description of what you do?

This is a really good question. In the past, people probably thought that a statistician is a very dry, boring discipline. No matter what, if I said I’m a statistician during a party, most likely people would walk away.

Nowadays biostatistics has become more interesting.

The first thing I would communicate to people is that my research expertise is in developing valid methodology to analyze data and deliver an answer to a particular research question. One example we encounter often is how a new experimental drug compares with the standard of care.

The second thing is more interesting. Let’s say our experimental drug prolongs life by one year, on average. That means some patients may have two years extra. Some patients may get six months and others may get worse compared to controls. Statisticians help you identify which patients would benefit most.

Clinical trial data typically identifies patients by their particular set of characteristics: ethnicity, age, prior treatment, and so forth. With the right methodology, we can use that data to identify which patients are likely to benefit beyond the standard of care and which are not, and therefore don’t really need this expensive, possibly toxic new therapy.

We call this personalized medicine. It becomes really important not only to individual patients’ health and quality of care, but also for managing healthcare expenditures globally.

We’ve been hearing about “personalized medicine” for decades. Are you saying biostatistics is the secret to better matching patients to treatments that work for them?

Any treatment may be beneficial for you, but may also have toxicity, right? You want to balance the risk versus the benefit. Let’s say a clinical trial finds that a particular group of patients may enjoy the benefit from the new treatment without much risk of toxicity, to the degree that maybe they can enjoy normal life again.

Patients who don’t belong to that group don’t have to waste their money and resources to pay for this new experimental treatment that is unlikely to benefit them and may, in fact, harm them. They can continue with standard care.

Over 45 years, we’ve developed novel statistical methodologies that are widely used in clinical trials to predict who will benefit and who will not from a particular treatment. My goal is to merge this statistical approach together with AI to build an even better prediction model. That’s my next five or ten years — if I live that long.

What would you like Harvard-affiliated researchers to know about the benefits of receiving a Harvard Catalyst biostats consultation?

I’m not sure investigators really appreciate how much they are likely to gain from this simple consultation, or how analytics can help them shape their research agenda. They should take advantage of the opportunity to tap into our experience.

“I’m not sure investigators really appreciate how much they are likely to gain from this simple consultation, or how analytics can help them shape their research agenda. They should take advantage of the opportunity to tap into our experience.”

Most of the time, the people who are referred to us for a Harvard Catalyst consultation are junior investigators who cannot afford to hire a statistician yet because they don’t have grants. Often, they’ve already collected some data, before they’ve even talked to us about how to design the study, and that data is usually not very interesting because it doesn’t really answer the questions they’re seeking to answer.

Investigators sometimes make analytics a lower priority or leave it to younger people because they think it should be routine. I think that is a big mistake. Junior investigators don’t always understand the whole picture. The clinical mentor should come with them for the consultation to ensure that we’re getting all the clinically relevant details that will help us devise the right methodology to actually answer the research question they’re asking.

So if I can make any recommendation, I would say that if you have a particular problem related to statistics, the best way to handle it is for the principal investigator of the project to also join the consultation, rather than just a junior researcher.

At 75, you’ve been teaching biostatistics at Harvard-Chan for 33 years. Any advice for younger generations?

You know, many years ago, a friend of mine who is a cardiologist in charge of clinical trials at a major medical school interviewed one of my former students for a position. But even though this person was overly qualified, my friend didn’t offer him a job, so I was a little unhappy about it.

I asked my friend why and he said: “I’m sorry to say this to you, but your student lost his curiosity.” He said once the sense of curiosity is lost, then everything becomes routine, and your life becomes really boring.

I use this word quite a bit now to encourage the younger generation. If you have curiosity, you can discover new things. Keep your curiosity.

Another thing I’ve learned from my own experience is that you have to be a little persistent when you are young. If you are really interested in a particular research agenda, don’t give up so easily. Put up your best effort until you exhaust it. If you then deem it hopeless, that’s okay.

Is retirement on the horizon for you?

A few years ago, I told my primary care doc of many years that I was thinking about retirement. She said: “LJ, I know you very well. I’m afraid you will be dead the week after you retire.” I asked why and she said I was someone who doesn’t know how to have hobbies. This is a part of my wife’s criticism of me also.

“If you have curiosity, you can discover new things. Keep your curiosity.”

They both know that I don’t really enjoy doing much other than learning new things every day from young people. For example, this morning I spent two hours on the computer to learn about neural networks from Chat GPT. It was a fascinating two hours; I learned so much. Every day that you learn something new is an opportunity to translate it to the younger generation and communicate an important area to work on.

I’m so excited every time I teach the younger generation. I still teach, and I still get really enthused by it. It’s a chance to be exposed to the younger generation, to understand what they think instead of staying in my own older-generation mode. If I retire, I’m not quite sure I will have an opportunity like this.

I hope my colleagues and friends will be caring enough to give me honest feedback if I become a hindrance in my profession, so that I may exit gracefully when it’s time. A gentle nudge of reality would allow me to contribute in more meaningful ways or pass the torch to those whose talents are better suited for the future. Though change can be difficult, maintaining dignity and goodwill is most important in the long run.