News & Highlights

Topics: Clinical & Translational Research, Education & Training, Five Questions, Health Disparities

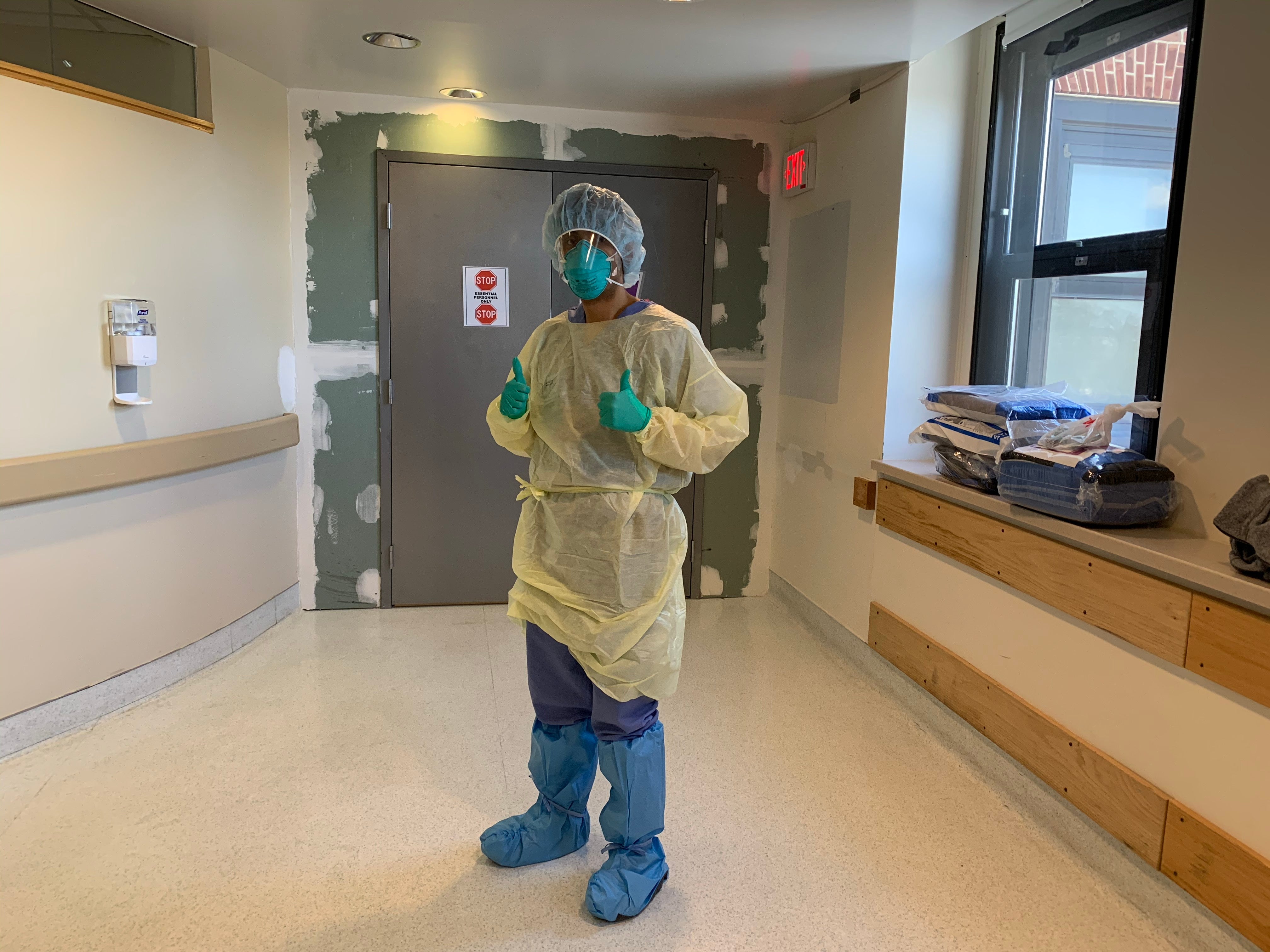

Five Questions with David Alejandro Sanchez

Our Visiting Research Internship Program (VRIP) alum discusses his summer at Harvard Medical School and shares his experience working with COVID-19 patients.

David Alejandro Sanchez, MD, is a resident in internal medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH). He was one of our visiting medical students from the summer of 2014 in the Visiting Research Internship Program (VRIP), mentored in the laboratory of Raymond Huang, MD, PhD, at BWH.

How influential was your VRIP experience?

My summer as a VRIP intern was my first real introduction to clinical research. I had done some prior infectious disease research, but it was all basic science focused in a wet lab environment. That summer, seeing research from a more translational perspective and all the available resources made me want to go to BWH for residency. I returned every year to the New England Science Symposium, thanks to Harvard Catalyst funding, and at one I met Joel Katz, MD, director of the Brigham’s internal medicine residency. Little did I know that a few years later I would be recruited to train at BWH by him personally. After the VRIP experience, I took a year off between my third and fourth year of medical school to do an NIH/HIV Vaccine Trials Network funded research fellowship. I then knew that I loved immunology.

“That summer, seeing research from a more translational perspective and all the available resources made me want to go to BWH for residency.”

How is COVID-19 affecting your residency?

I was recruited to do a shift the first weekend we opened the COVID-19 services at BWH. As residents, we’re still in training, but we were the first people to respond and care for these patients. We characterized their clinical presentation, the laboratory findings, and quickly realized how rapidly these patients can decompensate. We became quasi experts on COVID-19!

Neurology was supposed to be my elective block, but I got pulled to work the newly created COVID floors—the Special Pathogens Unit— the past two weeks (March 24-April 6). Most of our rotations, such as general medicine, cardiology, and oncology services are still up and running, but the patient census is much lower. Those that are on ambulatory blocks are now required to be on standby if needed by the special pathogens team, for both ICU and non-ICU services.

Both night shift teams were collectively admitting about 10 patients a night, which supersedes the number of patients we typically admit on a given night pre-pandemic. Many came in with low oxygen saturation and would go from requiring about two liters of supplemental oxygen up to six liters, and then needing intubation—all in the course of a few hours. I was sending someone to the ICU practically every night. We all were, which was very jarring.

We saw so many patients that we began noticing a constellation of findings that clued us in that a patient had COVID-19 before their nasal swab test resulted. Some of those findings have been described in the literature including low lymphocyte count, elevated inflammatory markers, and bilateral chest infiltrates on imaging but others less so. For example, many had rhabdomyolysis, which is essentially muscle breakdown secondary to the viral infection. We also noticed that in addition to the virus-related hypoxemia, many had pulmonary embolisms. Some people were coming in after an episode of syncope, a sudden loss of consciousness. That’s not typical with a viral illness.

What motivates you through the long days?

That I can have a positive impact on patients who are emotionally vulnerable. It’s a new disease and they’re scared. They do not have their families by their side which is particularly hard for me to witness as a provider. It is comforting to me that at least I’m trying to get them better and hopefully back to their families.

“Seeing these disparities motivates me every day to try and ameliorate them, because that’s the reason I went into medicine.”

The healthcare inequities affecting patients who are coming to the Brigham is also very important to me personally. We are seeing a disproportionate number of Latinx and black patients being admitted with COVID-19, which highlights the disparities that have always been present in our healthcare system. We know, for example, that black and Latinx people have a higher percentage of chronic diseases, which predisposes them to CoVID-19 infection, and that there are inequalities in access to care, which can lead to patients waiting until they’re really sick to call for help. Seeing these disparities motivates me every day to try and ameliorate them, because that’s the reason I went into medicine.

Is health disparities research part of your future plans?

I’m really interested in allergy/immunology and am planning to apply for the allergy/immunology fellowship in a few months. My goal is to become an asthma specialist and focus my research on healthcare inequities that affect Latinx and black asthmatics. We know from the data that people of color living in the inner city have higher rates of asthma and poorer health outcomes. If you’re Puerto Rican, you’re way more likely to have uncontrolled asthma and frequent asthma exacerbations that require a trip to the ER. The mortality rate for black asthmatics is significantly higher than for their white counterparts. My goal is to ameliorate these problems affecting my community by pursuing a research career addressing racial inequities in asthma.

What do you do to decompress?

I’m trying to exercise indoors in my apartment and do as many push-ups and sit ups as I can when I get a break from working in the hospital. I occasionally run outside too, keeping social distance. I also try to connect with my family and talk to my mom as often as I can. They’re another major driving force for why I do the work I do.