News & Highlights

Topics: Clinical & Translational Research, Education & Training

Boot Camp Kickstarts Clinical/Translational Career Transitions

Five Questions with Thomas Michel on MoD, AI, and a ‘protest accordion’ called Rosie.

Career and life transitions can be hard on anyone. Ask any physician-scientist trainee who’s been bouncing back and forth between clinical and research training along a decade-long path to a career in biomedical discovery. After finally completing years of clinical training, the transition back into biomedical research can be particularly tough. Science moves fast sometimes. A year ago, biomedical AI was barely on anyone’s radar, and as Thomas Michel, MD, PhD, quips: “Five years ago CRISPR was just something you wanted your potato chips to be.”

Michel knows first-hand how challenging it can be for physician-scientist trainees to navigate these transitions. That’s why, more than a decade ago, he launched the Models of Disease (MoD) Boot Camp. Today, graduates of the intensive summer training regimen–affectionately called the MoD Squad–lead independent labs, are rising leaders in academia, or have gone on to pursue meaningful careers in industry. Many pay back their boot camp training as guest faculty, helping the next generation of translational researchers get up to speed on hot new topics and novel methods to achieve success in whichever path they choose.

Michel is a professor of medicine (biochemistry) and a cardiovascular medicine specialist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. He also serves on the Leadership Council of the Harvard Medical School/Massachusetts Institute of Technology MD-PhD Program and is co-director of the Leder Human Biology and Translational Medicine Program for Harvard PhD students.

Models of Disease Boot Camp started in 2011 as your brainchild. What was your inspiration for it?

One of the key challenges in biomedical training is navigating the moments of transition. MD-PhD students go from being medical students to graduate students and back. Both MD-PhDs and MDs have the challenge of going from medical student to intern, then resident, then clinical fellow.

“The intention of the Models of Disease Boot Camp is to bring together young physician-scientists who are making these transitions and provide them with guidance that will allow them to pursue rewarding careers in translational and basic biomedical research.”

As challenging as those transitions are, none are quite as open-ended as the transition from completing one’s clinical training to returning to research training. At that point, after the fairly lockstep progression of rotations, clinics, and prescribed activities that encompass subspecialty clinical training, the trainee faces a vast world of research opportunities with relatively fewer formal structures to inform the next steps. And in returning to the basic and translational investigations that they pursued in their student days years ago, they find a new world.

The intention of the Models of Disease Boot Camp is to bring together young physician-scientists who are making these transitions and provide them with guidance that will allow them to pursue rewarding careers in translational and basic biomedical research. It’s a chance for them to learn what’s happened in biomedical science since the last time they wrote code or picked up a pipette and to find common cause with other people in the same boat. They also see how folks just a few years older than themselves transcended the challenges and went on to meaningful careers.

A central theme relevant to all levels of physician-scientist training is that the journey is the destination. For a student, it can be disheartening to look ahead at more than a decade of clinical and research training with classes, tests, rotations, and rigorous experiences both at the bench and at the bedside. But if the process can be seen as fulfilling and fascinating along the way, it’s a reward unto itself.

Thinking about last summer’s boot camp, what topics were generating excitement?

If there’s one hot new topic this year, it’s AI in biomedicine. Last summer, no one in the Boot Camp course was really talking seriously about the role of AI in biomedical research. This year, we had a session on it and discussed AI at length. We’ve also had more focus in recent years on working with big datasets. In the next year we will offer sessions on Python and other programming languages, not teaching them per se, but discussing how to understand and apply them to your research.

For the last four years, we’ve had sessions on gene editing with CRISPR-Cas9, examining how that technology has evolved. Before that the hot topic was probably single-cell RNA sequencing. Five years ago it was next-generation sequencing.

Changes seem to be much more fast-paced these days. From AI and Chat GPT to the advances in large data that have transformed biomedical investigation, things are happening with tremendous speed and power. Many of these techniques were not around when our current crop of boot camp trainees was in training. Back then, when someone said CRISPR, we thought about potato chips, not gene editing.

Is community building more important in translational science than in other areas of science?

I think it is as important as in many other fields yet might be harder to achieve, because the laboratory- or project-based investigator is ensconced within their laboratory or their project. When they’re training in the hospital or in their lab, their community of trainees and students is built around them. When they’re a principal investigator, they build their community focused on their research area. But going beyond one’s lab or department to seek out other individuals at similar career stages to find out what they’re up to is much harder, because people are so siloed.

Breaking down silos is particularly challenging in basic and translational biomedical investigation because both clinicians and researchers tend to be hyper-specialized. In the Models of Disease Boot Camp, our trainees are able to see the common paths by which biomedical scientists with different but complementary backgrounds and research interests have been able to move their work forward.

We’re fortunate to be in an environment where we have skilled instructors and investigators who are leading the charge in cutting-edge areas of translational science, nationally and internationally, and are willing to share their perspectives.

Are you seeing an exodus of clinical/translational scientists from academic research into industry, and does that worry you as a brain drain for academia?

“Changes seem to be much more fast-paced these days. From AI and Chat GPT to the advances in large data that have transformed biomedical investigation, things are happening with tremendous speed and power.”

I’m starting to see a trend where more of our biomedical research trainees are looking into options in industry. It may be a transient redirection of people’s career goals; we don’t know yet. I think it’s a healthy trend–up to a point–and it’s something we try to address in boot camp, to help people make the best decisions for themselves. We’re bringing in people who’ve made the transition to industry (and, in some cases back to academia) to talk about what influenced their decisions to leave academic biomedical research. What are those transitions like, when are they possible, and what are the challenges?

It’s always been challenging to build a career in academic medicine. Twenty years ago, biotech and “big pharma” started setting up shop in the Boston area with the express purpose of capitalizing on the local talent pool. Obviously, fundamental differences exist between a career in a for-profit corporation versus academic research, but perhaps not as many differences as you might expect or assume.

It’s a brain drain only if you close the door after people leave. If you leave the doors open, it’s actually a way of creating a community with a broader perspective. Bringing folks back in allows for an active interplay between people who are pursuing meaningful activities in pharma and biotech and their colleagues and trainees in academia. I think that’s a good thing.

You’re known for playing your accordion at protests and scientific meetings, including the infamous IgNobel Prize ceremony. Why do you call the accordion God’s instrument?

I think that the angels play accordions, not harps, which are basically very boring. Playing an accordion, one becomes a one-person band. It’s a very expressive instrument. You can play a wide variety of musical genres. The accordion can do vibrato like a cello or violin. It has a broad dynamic range and a surprising variety of musical timbres for a reed instrument. Of course there are good accordions and not-so-good accordions. A poorly made accordion sounds crappy.

Accordion players can also overdo it. I have a bumper sticker that reads: “Will play for free. Will stop for money.” I try to keep my exposure to a minimum, simply because I would rather that people think I’m not playing enough than that I’m playing too much.

When I go to scientific meetings, I’m often invited to bring along my accordion to play in the evenings after the scientific sessions end for the day. So I bring “Rosie,” my protest accordion because she is lighter than my concert accordion and fits in the overhead compartment on an airplane. I got Rosie back in 2017 when I was the organizer of the March for Science at Harvard and participated in several protest marches from HMS to the Boston Common. When we march from Harvard Medical School to Boston Common, Rosie comes along, and I play musical requests. She is red of course, and is named after some very important people: Rosie the Riveter, of course; Rosa Luxemburg, who was a late 19th century social activist; Rosalind Franklin, who should have won the Nobel prize for her work in DNA structure; and Rosa Parks.

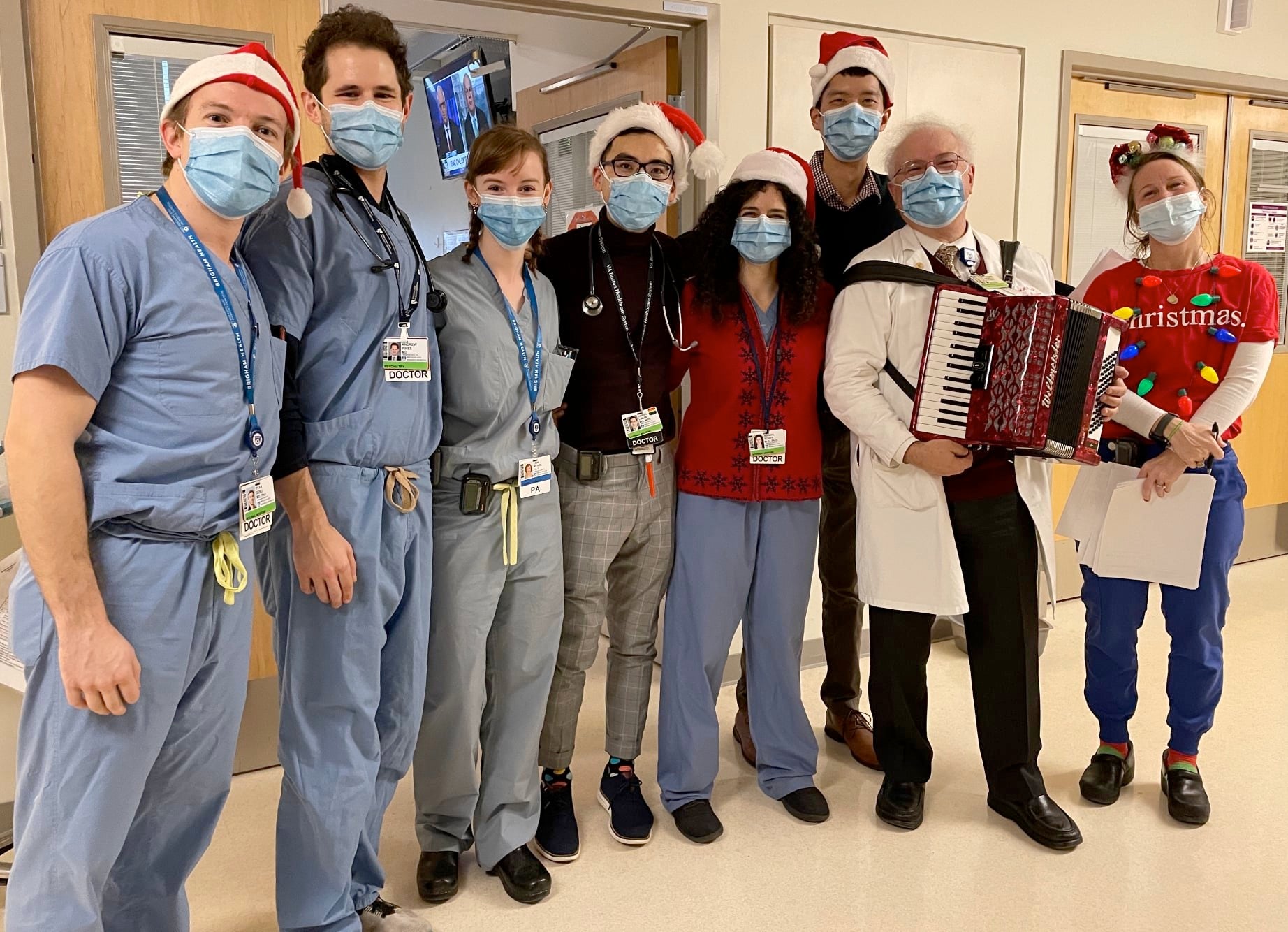

Rosie also is featured in my annual “Cardiotonics” Christmas gig at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, where she and I accompany the interns and residents singing holiday songs for inpatients who are too sick to go home on Christmas. Rosie is very versatile.